intro-to-github

A friendly introduction to GitHub as part of @OpenDataManchester's Pick N Mix series.

A friendly introduction to Version Control, Git and GitHub

Before we can dive into using GitHub, we need to talk about version control and Git.

Version control

Version control is a way of tracking changes to a document or collection of documents. You may have used word processing software that has a “changes,” “history” or “revisions” feature, which also allows you to see and revisit any changes to the document (such as Microsoft Word’s Track Changes, Google Docs’ version history, or LibreOffice’s Recording and Displaying Changes): this is a form of version control.

Version control helps to solve one of the main challenges in working with many people on a single project. Your collaborators may be spread around the world or working in the same room; they may be working simultaneously or asynchronously. No matter how your team is organised, the work of many contributors needs to be wrangled into a single project. Version control manages this process: it stores a history of changes and who made them, allowing you to revert or go back to earlier versions of those documents, and understand how contributions by different contributors have changed the project over time.

When we code, write text, or create any kind of content using computers, we end up with a collection of files in a folder or directory, also known as a repository or “repo”.

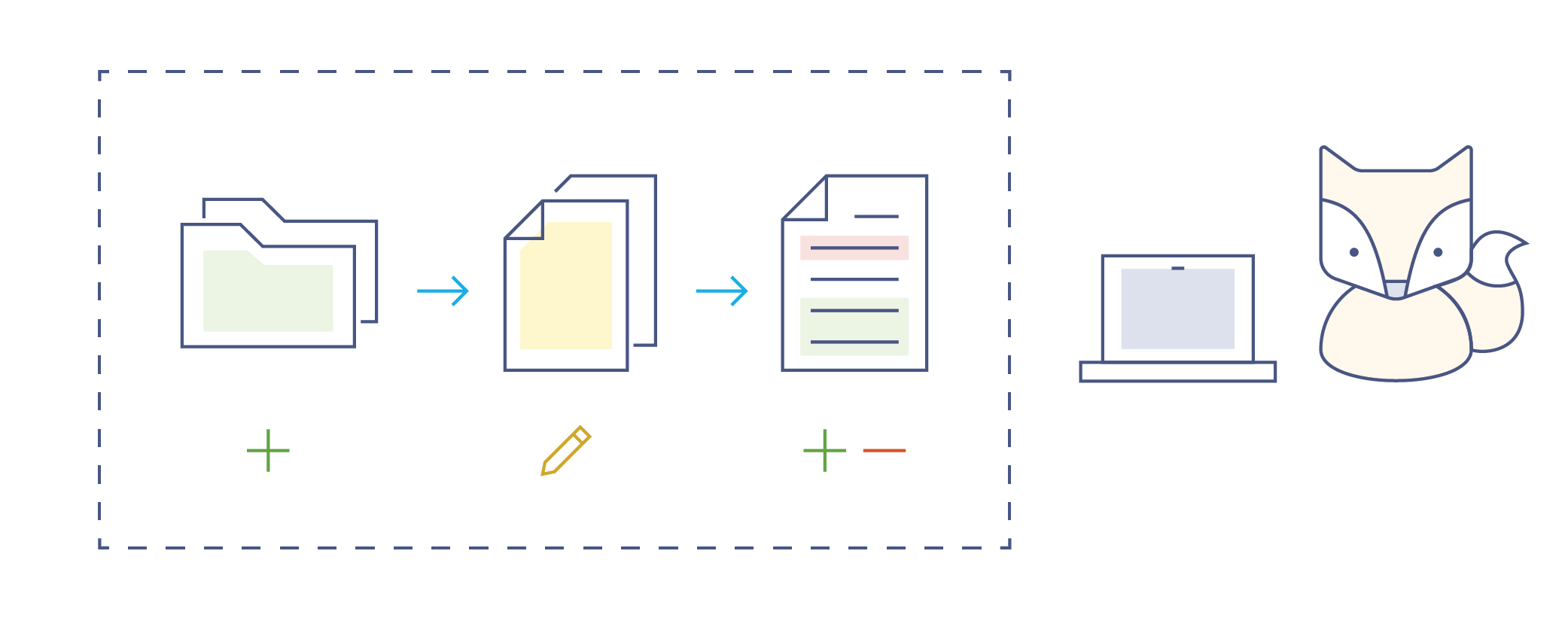

Even if you’re working independently, you’re probably going to make a lot of changes to your content or code as you go. For example, you will change some wording or functionality and leave others untouched - you will also make mistakes or change your mind while you experiment with new ideas!

As you make changes, you might make multiple copies of your files to preserve a version that’s working while you try to improve it or add functionality, but keeping track of all these versions and the differences between them becomes difficult. It also seems ridiculous to have multiple nearly-identical versions of the same document. (We want to avoid this situation.) If you work with others, maybe you email the different versions back and forth, renaming the file each time (code.py, code_rachael-comments.py, code-v2_rachael-comments.py, code-v2_working.py, code-v2_final-USE-THIS.py, and so on…). Whether you work alone or with others, if this situation looks familiar then you could benefit from version control.

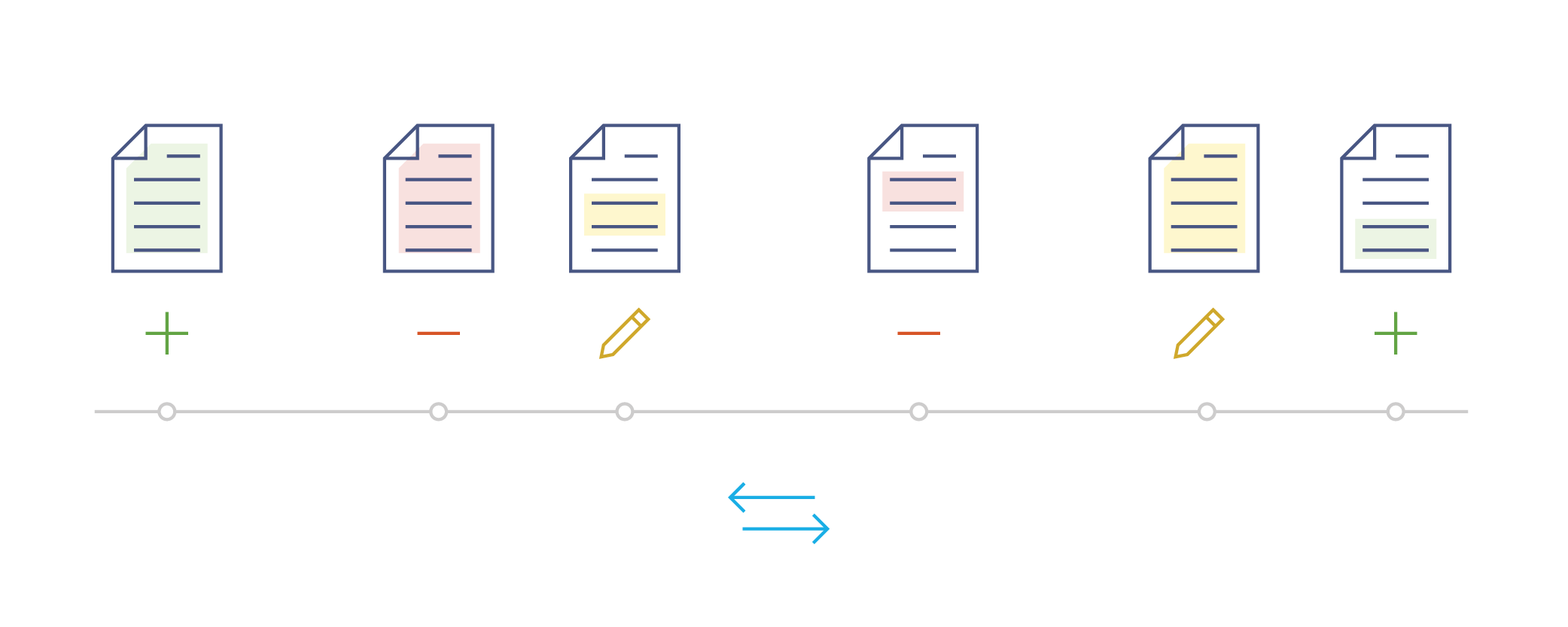

Version control systems start with a base version of the document and then record changes made each step of the way. Like a time machine, it can take you back to the moment your document was created, or to any other point in time when you or a collaborator saved changes to that document. With version control, you don’t save multiple copies of the document, you just save the timeline of changes of the document.

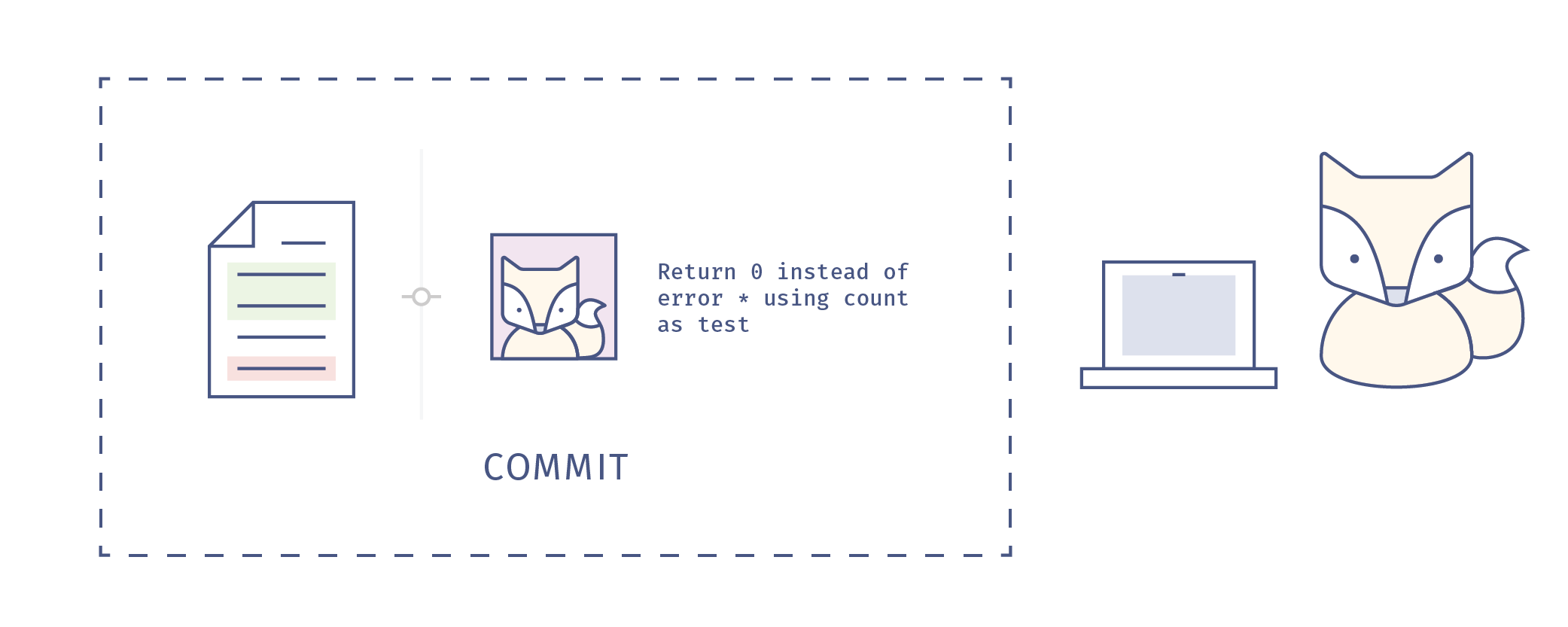

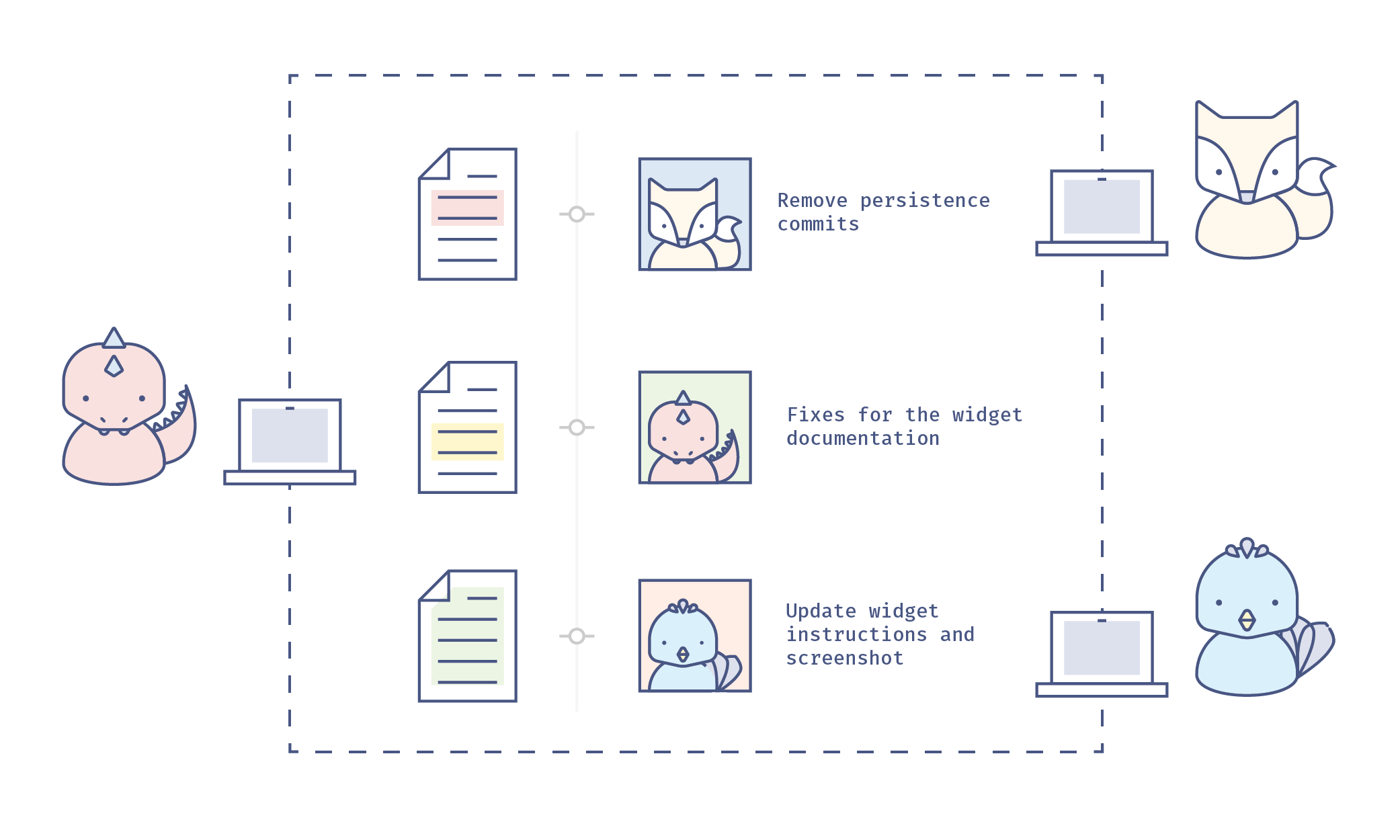

So what’s on the timeline? Each record of these changes is called a commit, which stores information on what changes were made, when and by whom. The timeline of the document is therefore a series of commits. Each commit should have an associated commit message, with a brief description of what changes were made and why.

When we share and work on projects with collaborators, managing the changes, or commits that multiple collaborators working in different places at different times make to a single set of documents becomes very, very important.

And when we’re working with multiple collaborators, everybody needs to know and understand what commits are being incorporated into the repository and why, so good communication also becomes very, very important. The great news is that there’s a piece of version control software to help us both manage and communicate with our collaborators about commits to our project, and that software is called Git.

Git

Git is an open source, distributed version control system for tracking changes in text files. It was originally developed in 2005 by Linus Torvalds, the author of the Linux operating system. It is command line software which works on your local computer and this is what it looks like to a user:

bash-3.2$ git --help

usage: git [--version] [--help] [-C <path>] [-c <name>=<value>]

[--exec-path[=<path>]] [--html-path] [--man-path] [--info-path]

[-p | --paginate | -P | --no-pager] [--no-replace-objects] [--bare]

[--git-dir=<path>] [--work-tree=<path>] [--namespace=<name>]

<command> [<args>]

These are common Git commands used in various situations:

start a working area (see also: git help tutorial)

clone Clone a repository into a new directory

init Create an empty Git repository or reinitialize an existing one

work on the current change (see also: git help everyday)

add Add file contents to the index

mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

restore Restore working tree files

rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

examine the history and state (see also: git help revisions)

bisect Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

grep Print lines matching a pattern

log Show commit logs

show Show various types of objects

status Show the working tree status

grow, mark and tweak your common history

branch List, create, or delete branches

commit Record changes to the repository

merge Join two or more development histories together

rebase Reapply commits on top of another base tip

reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

switch Switch branches

tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

collaborate (see also: git help workflows)

fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

pull Fetch from and integrate with another repository or a local branch

push Update remote refs along with associated objects

'git help -a' and 'git help -g' list available subcommands and some

concept guides. See 'git help <command>' or 'git help <concept>'

to read about a specific subcommand or concept.

See 'git help git' for an overview of the system.

This looks kind of scary, especially if you are a beginner. We can spot the commit command, which looks familiar - but clone? branch? merge? fetch? what? In general, you will only use a small subset of these commands over and over, so it helps to have a cheatsheet while you become familiar with the workflow. But it might be easier to get started with these concepts through a web interface instead of the command line. There are many offerings of Git repositories as a service, such as GitHub, Bitbucket and GitLab - we are going to focus on the most widely used: GitHub.

GitHub

GitHub is a platform for hosting and collaborating on Git repositories, and adds a web-based social and user interface to version control. GitHub provides a structure and space for communicating about collaborative work on open projects (although you can also have private repositories too). With bit of set-up, and a good workflow, you can make your project accessible and transparent, and create a respectful and productive working environment for your collaborators.

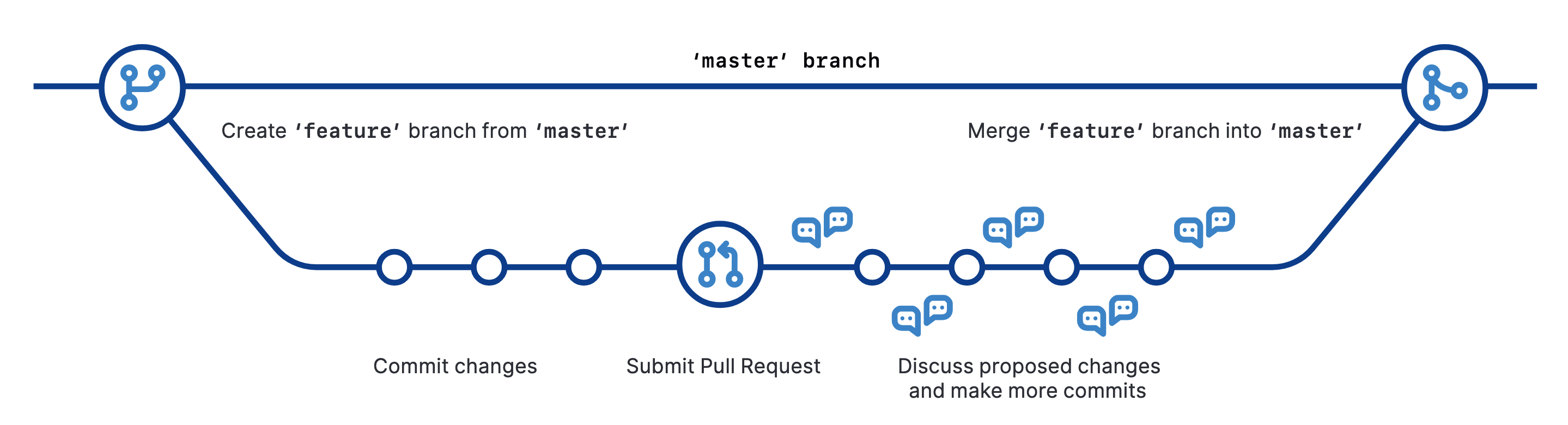

The basic GitHub workflow (called the “GitHub flow”) is built around core Git commands, and each step has distinct benefits when implemented:

- Create a branch from the repository.

- A branch is a copy of a repo that is contained within the orignal repo. Branches are used to work on a project features without altering the original or base repo.

- Add commits: make changes to (such as create, edit, rename, move, or delete) files in your repository.

- Open a pull request from your branch with your proposed changes to kick off a discussion.

- A pull request is a request to add a commit or collection of commits to a repository.

- Discuss, review and make changes (add more commits) on your branch as needed. Your pull request will update automatically.

- Merge the pull request once you are done making changes to the branch.

- Merging is the act of incorporating new changes (commits) into a repository.

One barrier to using Git and GitHub is that it can seem difficult to learn, because a lot of the terminology will be unfamiliar to newcomers. However, once you get used to the GitHub Flow, it will transform the way that you work - and the best way to learn is to practice.

tl;dr

- Version control is like an unlimited ‘undo’ button or time machine - it is very difficult to lose or break something because you can always revert back to a previous version.

- Version control allows many people to work together in parallel.

- Git is a command-line version control software that tracks all changes to a repository (a collection of documents).

- Revisions or saved changes to documents in a repository are called commits.

- GitHub is a service that hosts your repositories online and helps you work with contributors. GitHub adds a web-based social and user interface to version control.

Attribution

The content in this file has been adapted from:

- Mozilla Science Lab’s Study Group Orientation (including the images in the Version Control section), Licensed MPL 2.0

- Mozilla Science Lab’s GitHub Essentials, Licensed CC BY 4.0

- Software Carpentry’s Version Control with Git, Licensed CC BY 4.0

- GitHub Training Kit: Cheatsheets (inlcuding the image in the GitHub section), Licensed CC BY 4.0

Previous: About Me